- by Melissa Stern on March 24, 2015

-

Subodh Gupta, “This is not a fountain” (2011), old aluminium utensils, water, painted brass taps, PVC pipes, motor (all photos by the author for Hyperallergic)

Subodh Gupta, “This is not a fountain” (2011), old aluminium utensils, water, painted brass taps, PVC pipes, motor (all photos by the author for Hyperallergic)

New York is a big art city, with big art fairs, big museums, and lots of big concept art. There are exhibitions that fill museums with objects, like Maurizio Cattelan’s exhibition All at the Guggenheim Museum in 2011, and exhibitions that fill spaces with big concepts, like Marina Abramović’s 2010 exhibition at MoMA (The Artist Is Present). Some are more successful than others.

At Hauser & Wirth, Subodh Gupta has endeavored to pull off both, offering us compelling objects and a high concept. The title of the show, Seven Billion Light Years, refers both to the number of people presently alive on earth and to the idea of a universe of unfathomable size, time, and distance. Rarely does such a big concept play out in a gallery with the consistent clarity of Gupta’s show.

Subodh Gupta, “Aam,” (2015), painted bronze mangoes, found table (click to enlarge)

The exhibition dances between the enormity of India, and by extension the world, and the smallest of things that root Gupta to the earth. The show has a very deliberate trajectory, a visual and conceptual narrative that carries you from earth to sky. Gupta makes beautiful use of materials and themes focused on both his personal and cultural history. Many of the works use the common, cheap cooking vessels and tools found throughout India, where Gupta was born and raised, reminding the artist and us that food, water, and a home are the basic elements of life. Mangos and potatoes, two staples of the Indian diet, for both the rich and poor, are cast in bronze. These works are metaphorically temporal and permanent: the real food may rot, but the bronze endures.

Subodh Gupta, “This is not a fountain” (2011), detail

Subodh Gupta, “This is not a fountain” (2011), detail

Entering the first gallery we see an enormous sculpture made of piles upon piles of worn cooking implements: aluminum pots, teakettles, and blackened pans typical of Indian households all jumbled together in a monumental pile that measures almost 26 feet long and ten feet high. Water spigots incongruously stick up in random places and a continuous flow of water drains mysteriously into the pile. The piece, entitled “This is Not a Fountain” slyly refers to Magritte’s infamous painting “The Treachery of Images” and its tagline “Ceci, n’est pas une pipe” (“This is Not a Pipe”). Art is not reality, even art of the most pedestrian of objects. But of course, at the same time, the sculpture is a fountain and the gentle gurgling of water delights the ear, even as the eye wanders over what some might consider a giant pile of recyclables and in India the essentials of home life.

Subodh Gupta, “Seven Billion Light Years V” (2014), oil on canvas, found utensil, resin (click to enlarge)

Throughout the exhibition Gupta makes use of these common household objects, stringing them into a massive ten-foot long necklace, ironically called “Pearl,” or burying them in the ground in a work entitled “Pure,” in which the artist performed a ritualistic piece with the members of a small agricultural village in India. In these works, there is an interesting dialectic between the individual and the group — one pot and many pots that can be taken at face value or interpreted on other philosophical or political levels. There are those, for instance, who would see this entire show as a statement about class and economics in India. With Gupta’s work, there are multiple readings, and he leaves it up to the viewers to go in the direction that their own orientation takes them.

Subodh Gupta, “Pure (I)” (1999—2014), mixed media

As one moves toward the end of the exhibition, the earth is left behind with a room filled with four giant canvases entitled, “Seven Billion Light Years l, ll, lll, V.” They are based on a deceptively simple idea. Each painting consists of a beaten-up cooking vessel affixed to a huge (89 x 95 inches) canvas on which the artist has reproduced that same vessel, but blown up to stellar proportions. The vessels now look like planets, driving home the sense of duality that runs throughout this exhibition. Gupta captures the inextricable connection between the common and the universal, the earthbound and the celestial. The small moments beget the universal ones. The life of a lowly cooking pot contains the essence of the world.

Installation view of ‘Subodh Gupta: Seven Billion Light Years’ (click to enlarge)

It is in the three pieces entitled “Orange Thing,” “Untitled,” and “Hamid Ka Chimta” that Gupta uses the objects in a truly transcendent way. Three huge abstract sculptures, comprised of hundreds of brass, copper, and steel tongs fill one gallery space. They are very 1960s, mod, cool. Like supernovas, they shimmer in the light. The copper and brass pieces bend and move the light, from brilliant and reflective to a dark burnished interior. In contrast, the steel sculpture seems to suck the light into its rusted and dark interior.

Subodh Gupta, “Seven Billion Light Years” (2014–2015), film, 2 minutes (click to enlarge)

The journey concludes with a gleeful two-minute video about the life of a roti. We see the dough slapped down onto a convex iron cook top. The roti is then tossed in the air and we watch it travel in slow motion across the sky, past birds, past clouds and trees. The eye follows each delicate movement of the bread on the breeze as it floats downward back onto the cook top. Such a simple idea, and yet so lovely, lyrical, and gentle, the video synthesizes Gupta’s central themes: earth and universe, the individual and the group.

Subodh Gupta-“Orange Thing” detail (2014) steel, copper tongs, plastic

Subodh Gupta: Seven Billion Light Years continues at Hauser & Wirth (511 West 18th Street, Chelsea, Manhattan) through April 25.

Still from ‘Art War’

Still from ‘Art War’

‘The Green Wave’ poster

‘The Green Wave’ poster

Staff Banda Billi (2010)

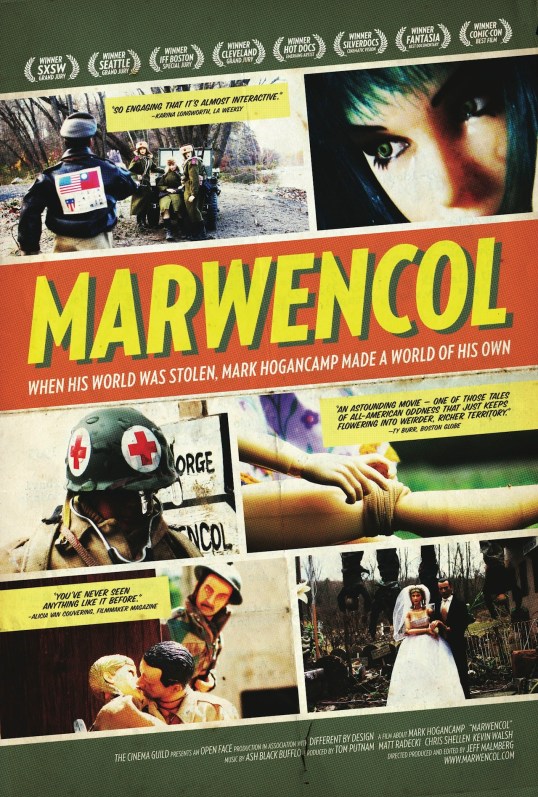

Staff Banda Billi (2010) ‘Marwencol’ poster

‘Marwencol’ poster Still from ‘Marwencol’ (2010)

Still from ‘Marwencol’ (2010)

Still from ‘Birth of the Living Dead’ (2013)

Still from ‘Birth of the Living Dead’ (2013) How to Draw a Bunny(courtesy Ray Johnson Estate)

How to Draw a Bunny(courtesy Ray Johnson Estate) The Red Chapel ( poster)

The Red Chapel ( poster)

Installation view of Pierre St-Jacques’ ‘The Exploration of Dead Ends’ at Station Independent Projects

Installation view of Pierre St-Jacques’ ‘The Exploration of Dead Ends’ at Station Independent Projects

Dan Miller, “Untitled (Lumber)” (2014), typewritten text on paper, 11″x30″

Dan Miller, “Untitled (Lumber)” (2014), typewritten text on paper, 11″x30″ Dan Miller, “Untitled (light pink ‘R’ and white on black)” (2011), acrylic on paper, 40″x50.5″

Dan Miller, “Untitled (light pink ‘R’ and white on black)” (2011), acrylic on paper, 40″x50.5″ Installation view of Creative Growth: Dan Miller exhibition at Ricco Maresca Gallery, New York

Installation view of Creative Growth: Dan Miller exhibition at Ricco Maresca Gallery, New York

A view of the Clemente installation with Clemente’s “Hunger” (1990) on the right, 93 1/2 x 96 1/2 in.,

A view of the Clemente installation with Clemente’s “Hunger” (1990) on the right, 93 1/2 x 96 1/2 in.,

New aluminum sculptures by Francesco Clemente (left to right), “Earth,” “Sun,” “Moon” (all 2014), Courtesy of the artist and

New aluminum sculptures by Francesco Clemente (left to right), “Earth,” “Sun,” “Moon” (all 2014), Courtesy of the artist and  Drawings from Francesco Clemente’s Sixteen Amulets for the Road series (2012–13), Courtesy of Francesco Clemente and Thomas Ammann Fine Art AG, Zurich

Drawings from Francesco Clemente’s Sixteen Amulets for the Road series (2012–13), Courtesy of Francesco Clemente and Thomas Ammann Fine Art AG, Zurich

Francesco Clemente, “Moon” (1980), gouache on twelve sheets of handmade Pondicherry paper joined with handwoven cotton strips, 96 1/4 x 91 in.The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Alan Wanzenberg in honor of Kynaston McShine, 2012

Francesco Clemente, “Moon” (1980), gouache on twelve sheets of handmade Pondicherry paper joined with handwoven cotton strips, 96 1/4 x 91 in.The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Alan Wanzenberg in honor of Kynaston McShine, 2012

Amy Sillman, “Me & Ugly Mountain” (2003), oil on canvas, 60 x 72 inches, collection of Jerome & Ellen Stern (photo by John Berens)

Amy Sillman, “Me & Ugly Mountain” (2003), oil on canvas, 60 x 72 inches, collection of Jerome & Ellen Stern (photo by John Berens)

Amy Sillman, “Elephant” (2005), oil on canvas, 78 x 66 inches, Collection Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art, Johnson County Community College, Overland Park, KS, Gift of Marti and Tony Oppenheimer and the Oppenheimer Brothers Foundation (photo by Gene Ogami) (click to enlarge)

Amy Sillman, “Elephant” (2005), oil on canvas, 78 x 66 inches, Collection Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art, Johnson County Community College, Overland Park, KS, Gift of Marti and Tony Oppenheimer and the Oppenheimer Brothers Foundation (photo by Gene Ogami) (click to enlarge) Amy Sillman, “C” (2007), oil on canvas, 45 x 39 inches, collection of Gary and Deborah Lucidon(photo by John Berens)

Amy Sillman, “C” (2007), oil on canvas, 45 x 39 inches, collection of Gary and Deborah Lucidon(photo by John Berens) An installation view, including (left to right): “Trawler” (2004), collection of Arthur Zeckendorf; “PS” (2013), courtesy of the artist and Sikkema Jenkins & Co.; “Unearth” (2003), collection of Barbara Lee, Cambridge, Massachusetts; “Ocean 1″ (1997), collection McKee Gallery, New York; and “Good Grief” (1998), collection of Dr. and Mrs. Lawrence Kessler.

An installation view, including (left to right): “Trawler” (2004), collection of Arthur Zeckendorf; “PS” (2013), courtesy of the artist and Sikkema Jenkins & Co.; “Unearth” (2003), collection of Barbara Lee, Cambridge, Massachusetts; “Ocean 1″ (1997), collection McKee Gallery, New York; and “Good Grief” (1998), collection of Dr. and Mrs. Lawrence Kessler. George Adams Gallery has mounted an exhibition of the work of George Ohr and Ron Nagle. Each had been known, in their time, for making work deemed groundbreaking and “outrageous.” George Ohr worked in the early 20th century, and turned pottery on its head, making vessels that toyed with all the traditional notions of pottery. He mixed glazes with wild enthusiasm, creating colors and textures that literally had never been seen before.

George Adams Gallery has mounted an exhibition of the work of George Ohr and Ron Nagle. Each had been known, in their time, for making work deemed groundbreaking and “outrageous.” George Ohr worked in the early 20th century, and turned pottery on its head, making vessels that toyed with all the traditional notions of pottery. He mixed glazes with wild enthusiasm, creating colors and textures that literally had never been seen before.