Published July 3 in Hyperallergic

The Wellcome Collection in London introduces four mixed-media installations in an immersive, collaborative show between artists and scientists.

Maria McKinney, Sire series, C-print, 147 X 220 cm. (all photos courtesy of the author for Hyperallergic)

LONDON — The Wellcome Collection in London has long been known for some of the most innovative and daring exhibitions imaginable. The museum is dedicated to the confluence of art and science, specifically to health and medicine. Sounds like a dry mission statement, but the creative curators of the museum have taken this vision to new and unexpected places.

Founded in 1936, the Wellcome Trust, under whose umbrella the museum sits, is financially and politically independent, enabling it to tackle controversial subjects without limits. In 2011, I saw an exhibition they mounted entitled Dirt: The filthy reality of everyday life that dealt with the world’s relationship with “filth,” aka: shit. It was brilliant in its scope and curatorial rigor.

The current exhibition, entitled Somewhere in Between, partners four visual artists with four scientists, each approaching a current issue in health or science. The exhibition features four very disparate subjects with which each artist has had personal experience. These subjects were matched with scientific experts in the respective fields. It is an ambitious undertaking with mixed results. There is no common thread between the four constructs, which may be part of the problem.

Maria McKinney, installation view of Sire at the Wellcome Collection

Sire, by artist Maria McKinney and scientists Michael Doherty and David MacHugh, is about the genetic engineering of bulls at an Irish stud farm. The bulls are genetically modified to emphasize the characteristics that will make these animals more efficient breeding machines. Ability to withstand climate change, increase in muscle mass, and lack of horns are desirable for future breeding stock. The artist has documented these bulls each wearing an intricate sculpture woven from insemination straws. She’s used traditional local corn weaving techniques to produce these futuristic fluorescent objects that the placid bulls each sport on their backs. Printed very large and in lush colors, the photos are oddly funny — big bulls meet DIY artisanal weaving. Several of these objects are exhibited as free-standing sculptures. They are very attractive. There is a passivity to the work that belies the undertone of the project. The back-story, presented in both text and audio to the public, bestows a much more ominous meaning upon the work, a story of genetic engineering taken to the extreme.

Maria McKinney, Sire series, C-print, 147 X 220 cm

The second of the four pairings sets out to examine the newly discovered neurological phenomenon of “mirror- touch synesthesia.” Synesthesia is a neurological condition in which the senses are blended. That is, you may associate letters or numbers with colors, or words and sounds with spatial locations on a consistent basis. This has been widely studied and documented. “Mirror-touch synesthesia” appears to take the notion one step further. To quote the exhibition catalogue, “A person with mirror-touch feels other people’s sensations of touch, both painful and pleasurable. When they observe touch, they sense it in their own body, as if experiencing it themselves.”

Daria Martin, At the Threshold (2014–15), 16-mm. film, 17.5 min.

Daria Martin has chosen to explore this phenomenon in two related 16-mm films: Sensorium Tests and At the Threshold. The former seeks to recreate the first tests that led to the discovery of this condition. The latter investigates the fictional relationship between a mother and son who share the condition. For Martin’s own reasons, she shot the second film as a 1950s-style melodrama. The films are being shown in two separate rooms that share a common entryway. I watched both of them twice and was unable to connect with the films, the subject matter, or the narrative, if there was one. The exhaustive text that accompanies this and all four of the projects is what finally gave me a hint as to what I was watching. Michael Banissy, the scientist with whom she collaborated, presents his work in an accompanying paper. It made me long for the writing of Oliver Sacks, who wrote extensively on these types of neurological oddities in a most erudite but accessible voice.

Daria Martin, Sensorium Tests (2012), 16-mm. film, 10 min.

For me, the installation’s extensive written annotations lead to a larger question about this kind of didactic museum exhibition. Can the art stand without the text? What happens when you have a visual art project that necessitates lengthy text to convey meaning to the viewer? While text can give additional insight into the work, the politics, or the artist’s intent, I prefer to be walloped by what I see. Having to then turn to the written explanation sucks the magical experience of looking at art right out of the room for me.

John Walter, Alien Sex Club, large paintings, acrylic on un-stretched canvas, various dimensions

Luckily, the final two projects in this exhibition stand more securely on their own as powerful visual statements. Alien Sex Club is a labyrinth of rooms and corridors, seeking to mimic the architecture of gay cruising spaces (according to the artist’s description). This multimedia, at times almost psychedelic, installation explores a sub-culture of gay sex behavior post-HIV anti-viral treatments. This project was done in tandem with a primary infectious diseases researcher and a team of sexual health professionals from many parts of the UK. This installation is as excessive as the first two artistic pairings are spare. Videos, sex toys, viewing booths, drawing, wallpaper — this is a dizzying array of ideas, colors, and objects.

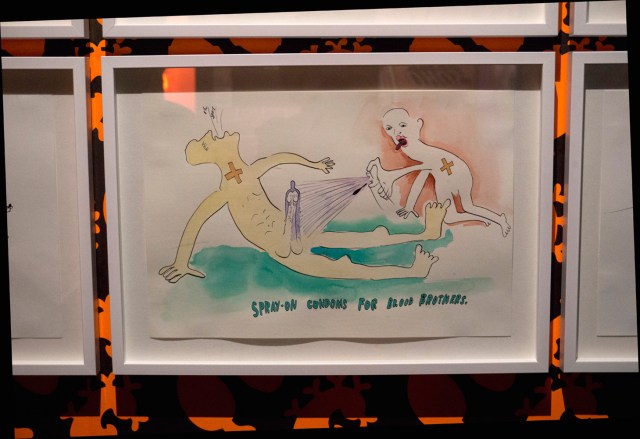

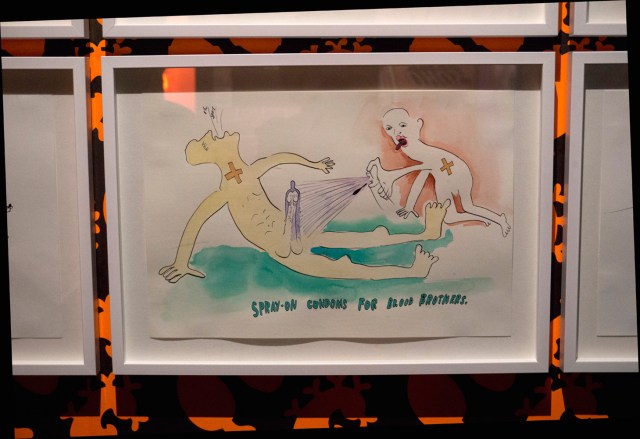

John Walter, Alien Sex Club, drawing from Big Book, mixed media, 120 x 150 cm.

John Walter has created a vibrant universe of “post-HIV” gay life from an admittedly personal point of view. In his work, text is used as a dictionary for explaining some of the imagery of the Alien Sex Club, rather than as an explanatory crutch. The artist envisions a kind of parallel universe to ours, populated with “bugs”(the virus) and the rigid geometry of the retro virus pills, as well as icons like Keith Haring and Alistair Crowley.

John Walter, Alien Sex Club, drawing from Big Book, mixed media, 120 x 150 cm.

The installation in its entirety is a giddy romp; I found the most affecting pieces to be a series of mixed-media drawings in a piece entitled “Big Book” that acts as an instructive and informative “Bible” of the Alien Sex Club. The drawings are beautiful, wry, and sometimes sad. They pack an emotional punch that isn’t present in any of the other pieces.

Martina Amati, Under (2015), 3-channel video projection, 5-channel audio, color, 11 mins., looped

Martina Amati, Under (2015), 3-channel video projection, 5-channel audio, color, 11 mins., looped

The final installation in this quartet is quite literally breathtaking. Martina Amati is a free diver. That is, she free dives deep into the Red Sea without an air supply. She has trained her body to withstand the physiological and psychological pressures of doing something that is life-threatening and arguably insane. Her immersive installation of three wall-sized projections is entitled Under. They explore the three ways that free diving is measured — time, distance, and depth. The artist appears in each of the videos, which are shot and projected in such a way that you feel you are in the water with her. She sinks deep into the sea. She dances seemingly in elegant slow motion around a guide rope. The moving images are mesmerizing and incredibly beautiful. Meanwhile, my mind is racing: “Oh my god, how is she that deeply under the sea without any air?” The beauty of the videos belies the danger of the act. It is literally death-defying art. Two films are shown simultaneously in one room, the third on its own. There are accompanying still photographs from the videos exhibited on their own.

Martina Amati, Under (2015), 3-channel video projection, 5-channel audio, color, 11 mins., looped

Amati’s collaboration with scientist Kevin Fong was clearly one that really clicked. Each has written a succinct and poetic essay about their experience of working together. In this case, the art works completely independent of the text. The text becomes an additional poetic device to discuss both the mysteries of what the human body is capable of and the poetry of collaboration.

Though a bit of a mixed bag, the Wellcome Collection doesn’t disappoint in its eagerness to embrace new artistic possibilities at the growing intersection of art and science. In this era of blockbuster, crowd-pleasing mega-shows it is a delight to experience a cultural institution that is willing to challenge its audience.

Martina Amati, stills from Under (2018), C-prints, framed

Somewhere in Between is on display at the Wellcome Collection (183 Euston Rd, Kings Cross, London) through August 27.

Dawn DeDeaux, “The Mantle (I’ve Seen the Future and It Was Yesterday)” (2016–17), aluminum mantle with objects, and “Broken Mirror” (2017), transparency on convex mirror (all photos by the author for Hyperallergic)

Dawn DeDeaux, “The Mantle (I’ve Seen the Future and It Was Yesterday)” (2016–17), aluminum mantle with objects, and “Broken Mirror” (2017), transparency on convex mirror (all photos by the author for Hyperallergic)

Vivian Sundaram, “Terraoptics Split Open” (2016), 30 x 30 inches, Archival Pigment Print on Hahnemuhle FineArt Baryta paper, installation view at Sepia Eye (all photos by the author for Hyperallergic)

Vivian Sundaram, “Terraoptics Split Open” (2016), 30 x 30 inches, Archival Pigment Print on Hahnemuhle FineArt Baryta paper, installation view at Sepia Eye (all photos by the author for Hyperallergic) Vivian Sundaram, “Terraoptics Burnt Mound” (2016), 48 x 34 inches/ 48 x 34 inches, Archival Pigment Print on Hahnemuhle FineArt Baryta paper, installation view at Sepia Eye

Vivian Sundaram, “Terraoptics Burnt Mound” (2016), 48 x 34 inches/ 48 x 34 inches, Archival Pigment Print on Hahnemuhle FineArt Baryta paper, installation view at Sepia Eye

Vivian Sundaram, “Terraoptics #077” (2016) (detail), 30 x 30 inches, Archival Pigment Print on Hahnemuhle FineArt Baryta paper, installation view.

Vivian Sundaram, “Terraoptics #077” (2016) (detail), 30 x 30 inches, Archival Pigment Print on Hahnemuhle FineArt Baryta paper, installation view.