Oct. 21, 2021 ( yeah I know, I’m posting a wee bit late!) in Artcritical

Installation shot of the exhibition under review, with Karon Davis’s Double Dutch Girls (2021) in the foreground. Courtesy of Jack Shainman Gallery

Jack Shainman opened The School in Kinderhook, NY as a satellite space to his New York City galleries in 2014. A 30,000 square foot former schoolhouse built in 1929, it was renovated by architect Antonio Torrecillas. Some elements have been left intact: girls and boys bathrooms, fixtures removed, are still painted in the pink and blue of the era, the decaying plaster walls sealed permanently in their beautiful, melancholy state, in sharp contrast to the “white box” galleries elsewhere . It is worth the 2-1/2 hour drive from the city just to see the building.

This summer, the Schoolhouse presented a 22-artist group exhibition, “Feedback,”curated by Helen Molesworth “Feedback is filled with art works by artists who I’ve been following for a while,” the curator has written. “In other words, artists I ‘like’ and who I have asked to gather together today to form an assembly, a class, a chorus.”

According to Molesworth, the idea for the exhibition was triggered by first experiencing the audio piece by Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller that now greets visitors upon entering The School. When a visitor steps on the “wah wah” pedal, the amplifier placed behind it begins to play a Jimi Hendrix-inspired version of the Star Spangled Banner that is amplified to the point of aural pain. When I visited there was a guard stationed nearby to turn it off immediately, so unbearable is the noise: An inauspicious introduction to an exhibition that is in many ways a gentle exploration of contemporary visions. Among its other meanings, “feedback” is a term for the sound generated by this pedal.

Mixing and matching in each room, Molesworth has installed works to create small universes where the artworks are orbiting each other in meaningful ways and in turn responding to the architectural implications of each space.

Kerry James Marshall, Ecce Homo, 2008-14. Acrylic on PVC panel, 9 x 24 inches. Courtesy of Jack Shainman Gallery

Kerry James Marshall, Ecce Homo, 2008-14. Acrylic on PVC panel, 9 x 24 inches. Courtesy of Jack Shainman Gallery

One of the most successful in what the checklist calls the “southeast unfinished classroom,” an eerie space with peeling and pockmarked blue paint on the old plaster walls. Molesworth has assembled the works into a tableau of relationships that carry the echoes of an old schoolroom. Taylor Davis has a trio of three watercolors that riff on the American flag (ever present in American classrooms of the past), their stars and stripes morphed into calligraphic poems that float across the page. The room is bookended by two powerful paintings: “Ecco Homo by Kerry James Marshall and The Treasures by Lynette Yiadom-Boakye. Each portrays a young Black man, perhaps teenaged, in very different states of mind, looking at each other from across the room. Both send mixed messages of slavery and freedom.

Marshall’s painting, with his typical attention to crisp detail, presents a young man adorned with a massive gold chain encircling his neck which can be read as a golden yoke. He meets the viewer’s eye with what can be taken, equally, as pride and a plea for rescue.

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, The Treasures, 2012. Oil on canvas, 9-1/2 x 51-1/8 inches. Courtesy of Jack Shainman Gallery

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, The Treasures, 2012. Oil on canvas, 9-1/2 x 51-1/8 inches. Courtesy of Jack Shainman Gallery

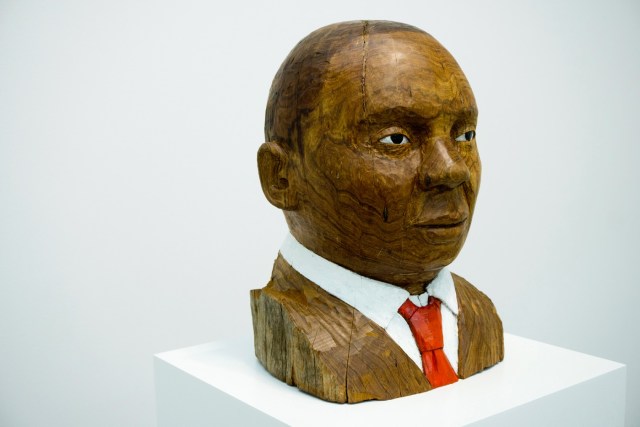

Rose Simpson- Storyteller. Ceramic, steel

But it’s the two freestanding sculptures that, for me, tie the theme of the room together. Rose B. Simpson, whose masterful ceramic and mixed media figures populate several rooms in the exhibition, has a piece here entitled Storyteller. A medium-sized figure, glazed in matte yellow ochre and painted with dark simplified symbols, sits on the floor. Out of their mouth erupts a steel framework upon which are perched small terra cotta figures. Huddled together they reach, cuddle, whisper and climb on one another. The work is at once evocative of pre-Columbian and Southwest American pottery forms and totally contemporary. The sculpture personifies the passing of knowledge, albeit in a different kind of classroom.

Karon Davis- Game:9:43 am ( Frankie) . Plaster, found objects. Lifesize

Karon Davis’s Game: 943am (Frankie) is provocative and open-ended like other works in this room, disturbing but alternatively perhaps amusing. An elementary age schoolgirl, fabricated out of stark white plaster, sits under a vintage school desk looking upward with human eyes. An open schoolbook lies on the desk above her, as if abandoned hastily. Evocative of so many things at once. There used to be “fallout drills” in U.S. schools; upon the sound of an alarm we would all scuttle under our desks for protection from the possible atomic bomb that was about to land on us. Hardly reassuring, but a potent image of the era. Is our young girl participating in a drill or is she hiding from an unseen threat? Or is it a game of hide and seek?

Feedback is an ambitious exhibition whose success lies in imagining the school space as a totality. The exhibition is especially resonant as American’s rethink their relationship to public spaces and the nature of childhood and schooling. Feedback is an endearing and affecting artistic take on the late-summer theme of “Back to School.”

Feedback at Jack Shainman/The School runs through October 30, 2021, 25 Broad Street, Kinderhook, NY 12106. jackshainman.com